Anthony was born in 1820 in Massachusetts. She was raised as a Quaker and her belief in equality inspired and guided her throughout her life’s work.

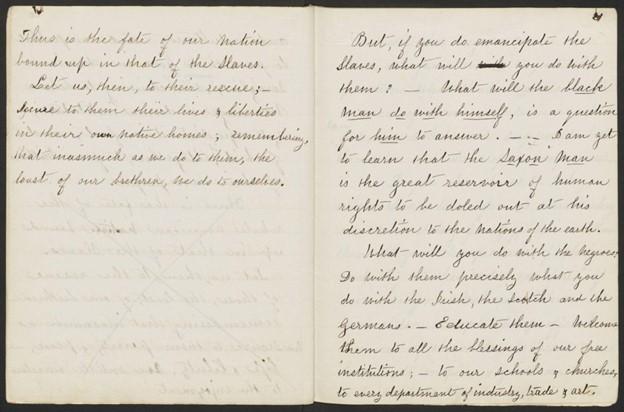

Anthony fought for the abolition of slavery. In 1856, she served as an American Anti-Slavery Society agent, making speeches, organizing meetings, and distributing pamphlets.

In 1851, Anthony met Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the two suffragists worked to gain independence and equality for women for the rest of their lives. She traveled around the country advocating for women’s rights and lobbied Congress every year until her death.

She died in 1906, fourteen years before many women were given the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

Susan B. Anthony was born on February 15, 1820, near Adams, Massachusetts to Daniel Anthony and Lucy Anthony. She became a part of the rapidly expanding young American republic founded less than fifty years before. As settlers continued to push westward, the expansion of the nation led to questions concerning the establishment of slavery in the West. This was exemplified by the passage of the Missouri Compromise in the year of her birth.

The industrial revolution was beginning in America. Cotton cloth was the new sensation and the demand for it began to steadily grow. In fact, Anthony’s father built a cotton factory and employed many young women, some of whom boarded with the family. Anthony even worked at the mill with one of her sisters, splitting their wages. But an early age, Anthony wondered why her father would not employ a woman as an overseer in the factory (International Council of Women 163).

Anthony was influenced by the political, social and economic issues of her time, but was especially influenced by the religious views her family instilled in her from an early age. Her father Daniel was a member of The Society of Friends , or Quakers. He was concerned over the westward expansion of slavery, and she often heard him say that he tried to avoid purchasing cotton raised by enslaved labor. This early understanding of the horrors of slavery stayed with Anthony throughout her life (Lutz 10).

A few weeks after her thirteenth birthday, Anthony officially became a member of the Society of Friends. One of their main values is “the equality of all people before God” (Lutz 11). Quakers not only encouraged but demanded education for both boys and girls. As soon as Anthony was old enough, she worked and taught in the “home school” during the summer, educating younger children. Further expanding her education in 1837, Anthony's father sent her to the Friends’ Seminary near Philadelphia, where she studied a variety of subjects: arithmetic, algebra, literature, chemistry, philosophy, physiology, astronomy, and bookkeeping.

In 1845, the Anthony family moved to Rochester, New York, where they became active in the anti-slavery movement. Their home served as a meetinghouse almost every Sunday, and attendees included famous abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison .

In her mid-thirties she was invited to join the anti-slavery lecture circuit during a defining period in US history – the decade of crisis before the Civil War. During this time, Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the new Fugitive Slave Law was passed, and the pending Kansas-Nebraska Act infuriated northerners and abolitionists.

Anthony spoke out against slavery wherever she could find an audience. She even challenged Abraham Lincoln’s moderate position on slavery in 1861, demanding “no compromise with slaveholders.” It was a chapter in her life she would later call “The Winter of Mobs”. In fact, in Syracuse, New York, a mob burned her in effigy and her “body” was dragged through the streets (Sherr 30).

Later, in 1863, Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucy Stone formed the Women’s Loyal National League to press for a Constitutional amendment to abolish slavery. This goal was finally realized with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

Susan B. Anthony Papers, 1815-1961. Manuscript speeches. Re: slavery, ca.1862. A-143, folder 28. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America. Harvard University. Accessed 28 June 2024. https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:rad.schl:8919572

In 1848, Anthony began work as a teacher in New York and became involved in the teacher’s union. Through this, she discovered that male teachers received a monthly salary of $10, while the female teachers only earned $2.50 a month. This experience with the teacher’s union, along with her previous abolition activism and Quaker values, inspired her dedication to gender equality. She would go on to become greatly involved in the fight for women’s suffrage, or the right for women to vote in elections.

In 1851, she met Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Stanton was known for organizing the first woman's rights convention, the Seneca Falls Convention , in 1848. Stanton and Anthony formed a friendship and partnership that lasted the rest of their lives. While Stanton, a mother of seven children, would often stay home to write and organize, single Anthony had the freedom to travel as an activist. Though she received several proposals of marriage throughout her life, Anthony never married (Sherr 14).

In the 1850s and 60s, Anthony was extremely active in the women’s rights movement. She served on committees, spoke at conventions, created women’s associations, and campaigned for women’s property rights.

In 1868, Anthony and Stanton founded the American Equal Rights Association and became editors of its newspaper, The Revolution. Anthony built subscriptions, solicited advertisements, and took copies to the printer. The paper discussed suffrage, education, marriage and divorce, equal pay, eight-hour workdays, and labor and financial policy.

It was at this point that the suffrage movement divided over the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments. The 14th Amendment was the first mention of gender in the Constitution, granting all male citizens 21 years old the right to vote. The 15th Amendment stated that the right to vote would not be denied due to race. The passage of both meant that Black men would have the right to vote, but not Black women or other women of color.

Anthony and others supported the 15th Amendment only if it included universal suffrage for all, regardless of race and gender. Activists like Frederick Douglass and Lucy Stone still supported the 15th Amendment, because they thought it would be impossible to get the vote for both Black men and white women at the same time. But Stanton and Anthony disagreed and opposed the amendment, believing that if anyone deserved the vote, it was the educated white women first. Though Anthony had previously lobbied for the abolition of slavery and the rights of enslaved African Americans, she still adopted the racist positions used by many other white women at that time to support her goal of women’s suffrage.

To focus attention on women’s suffrage, and in reaction to the exclusion of women in the 15th Amendment, Anthony called together the first suffrage convention ever held in Washington, DC in January of 1869. Then, on March 15, 1869, the first federal women’s suffrage amendment was proposed in Congress for consideration (Lutz 115).

That same year, Anthony and Stanton split from other suffragists like Lucy Stone and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and created the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) which opposed the 15th Amendment since it did not include gender. Anthony adamantly continued her opposition as editor of The Revolution. Stone, Watkins Harper, and other suffragists formed the rival organization, American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which supported the 15th Amendment, while also advocating for women’s suffrage in consequent legislation. These opposing groups vied for support up until the 15th Amendment was finally ratified in 1870. The NWSA then refocused its energy to push for a separate constitutional amendment aimed at specifically securing women the right to vote.

After the Civil War, suffragists had four major legal strategies: campaigning at the federal and state level; lobbying to supportive voters and their casting of ballots; proposing a new women’s suffrage Constitutional amendment; and litigating in court to test women’s rights under the existing Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

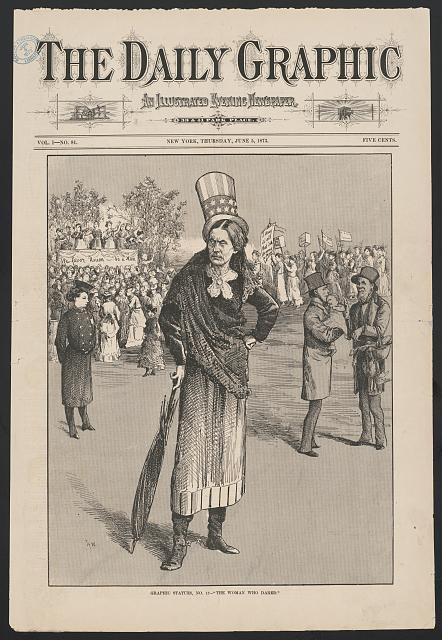

Anthony preached militancy to women throughout the presidential campaign of 1872, urging them to claim their rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments by registering to vote in every state of the Union (Lutz 140). During the campaign, Anthony, her sisters and a close Quaker friend walked to a nearby barber shop to register to vote and eleven other women joined them. The women boldly entered and the bewildered male registrars allowed them to sign in. Then on the morning of November 5th, she cast her first and only presidential ballot for the Republican candidate Ulysses Grant and two congressmen. Weeks later, on November 18th, she was arrested at her home in Rochester, New York by a US marshal and put on trial at the Ontario County Courthouse. She and her colleagues all pleaded “not guilty” and bail was set.

For three weeks she traveled around the county, delivering lectures on the “crime of a citizen voting in an election”. The prosecutor complained and the trial was moved to another county. On June 17, 1873, Anthony was tried by 12 white men in the jury box, but the judge made his decision before even hearing the trial. The judge directed the jury that their verdict declare her guilty. Anthony, forbidden to defend herself until after the verdict, was convicted and fined $100, which she refused to pay. The judge purposely did not sentence her to prison time, which ended her opportunity to appeal her case. Anthony was hoping an appeal could make its way to the US Supreme Court. Although her plan did not materialize, the trial made national headlines and expanded discussion of the movement.

Wust, Thomas, Artist. Graphic statues, no. 17 "the woman who dared" / / Th. W. United States, 1873. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/95512461/.

During the 1880s, Anthony focused on documenting the history of the movement she helped create. Recording women’s history for future generations was a project that had been in the minds of Anthony and Stanton for a long time. Both looked upon women’s fight for political participation as a potent force in strengthening democracy and one to be emphasized in history. Anthony was convinced that if women close to the facts did not record them now, they would be forgotten and misinterpreted by future historians (Lutz 164).

Anthony, Stanton, and Matilda Joslin Gage published the History of Woman Suffrage Volume I in 1881, followed by Volumes II, II, and IV in 1882, 1885, and 1902. As Stanton stated, “We have furnished the bricks and mortar for some future architect to rear a beautiful edifice.” (Lutz 166

In 1890, the National Woman Suffrage Association merged with the American Woman Suffrage Association, which was advocating for state-by-state enfranchisement of women. Stanton became the first president of the new organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association, with Anthony subsequently elected its president in 1892. Anthony was also instrumental in creating the International Council of Women and in assisting in organizing the World’s Congress of Representative Women at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

In 1898, The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, A Story of the Evolution of the Status of Women was published by Ida Husted Harper at Anthony’s request. Anthony also created a press bureau to increase coverage of women's suffrage in the national and local press. This same year, Anthony announced her intention to retire from the National American Association. During the last year of her presidency, she warned the new generation of suffragists not to expect their cause to triumph merely because it was just. After Anthony’s retirement, Carrie Chapman Catt was elected as the new president of the organization. Anthony remarked “New conditions bring new duties. These new duties, these changed conditions, demand stronger hands, younger heads, and fresher hearts. In Mrs. Catt, you have my ideal leader. I present to you my successor.” (Lutz 197)

In 1905, she met with President Theodore Roosevelt in Washington DC to discuss the submission of a suffrage amendment to Congress. She attended hearings in DC and gave her “Failure is Impossible” speech at her 86th birthday celebration. “There have been others also just as true and devoted to the cause - I wish I could name every one - but with such women consecrating their lives, failure is impossible!” (Sherr 234)

Susan B. Anthony died on March 13, 1906 from heart failure and pneumonia at her Rochester home. She did not live to see the passage of the 19 th Amendment . However, in recognition of her role in bringing about its fruition, the amendment was widely heralded as the “Susan B. Anthony amendment” and was ratified in 1920. As such, it stood as a tribute to Anthony’s integrity, determination, and influence. The fruits of her labor would enable many women to play an integral role in shaping US society for generations to come.