Fifty years ago, the Voting Rights Act targeted the laws and practices of Jim Crow. Here’s where the name came from.

By Becky Little August 6, 2015 • 5 min readIn 1944, the Detroit chapter of the NAACP held a mock-funeral for him. In 1963, participants in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom symbolically buried him. Racial discrimination existed throughout the United States in the 20th century, but it had a special name in the South—Jim Crow.

Fifty years ago this Thursday, President Lyndon B. Johnson tried to bury Jim Crow by signing the the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law. The Voting Rights Act and its predecessor, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, fought racial discrimination in the South by banning segregation in public accommodations and outlawing the poll taxes and tests that were used to stop African Americans from voting.

Today, we still use “Jim Crow” to describe that system of segregation and discrimination in the South. But the system’s namesake isn’t actually southern. Jim Crow came from the North.

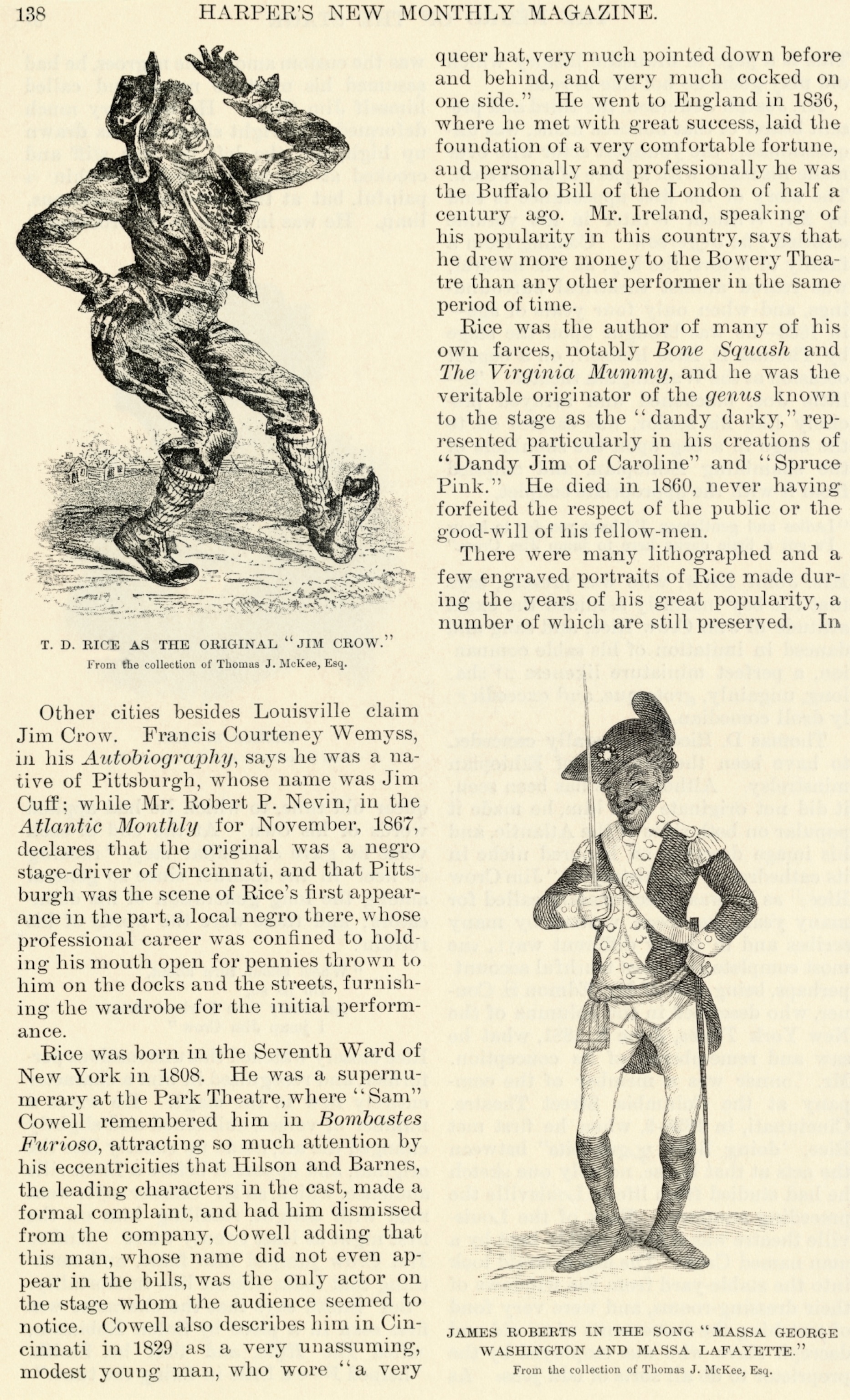

Thomas Dartmouth Rice, a white man, was born in New York City in 1808. He devoted himself to the theater in his twenties, and in the early 1830s, he began performing the act that would make him famous: he painted his face black and did a song and dance he claimed were inspired by a slave he saw. The act was called “Jump, Jim Crow” (or “Jumping Jim Crow”).

“He would put on not only blackface makeup, but shabby dress that imitated in his mind—and white people’s minds of the time—the dress and aspect and demeanor of the southern enslaved black person,” says Eric Lott, author of Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class and professor of English and American Studies at the City University of New York Graduate Center.

Rice’s routine was a hit in New York City, one of many of places in the North where working-class whites could see blackface minstrelsy, which was quickly becoming a dominant form of theater and a leading source for popular music in America. Rice took his act on tour, even going as far as England; and as his popularity grew, his stage name seeped into the culture.

“‘Jumping Jim Crow’ and just ‘Jim Crow’ generally sort of became shorthand—or one shorthand, anyway—for describing African Americans in this country,” says Lott.

“So much so,” he says, “that by the time of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was twenty years later in 1852,” one character refers to another as Jim Crow. (In a strange full-circle, Rice later played Uncle Tom in blackface stage adaptations of the novel, which often reversed the book’s abolitionist message.)

Regardless of whether the term “Jim Crow” existed before Rice took it to the stage, his act helped popularize it as a derogatory term for African Americans. To call someone “Jim Crow” wasn’t just to point out his or her skin color: it was to reduce that person to the kind of caricature that Rice performed on stage.

After the Civil War, southern states passed laws that discriminated against newly freed African Americans; and as early as the 1890s, these laws had gained a nickname. In 1899, North Carolina’s Goldsboro Daily Argus published an article subtitled “How ‘Capt. Tilley’ of the A. & N.C. Road Enforces the Jim Crow Law.”

“Travelers on the Atlantic & North Carolina Railroad during the present month have noted the drawing of the color line in the passenger coaches,” reported the paper. “Captain Tilley … is unceasing in his efforts to see that the color line, otherwise the Jim Crow law, is literally and fearfully enforced.”

Experts don’t really know how a racist performance in the North came to represent racist laws and policies in the South. But they can speculate.

Since the phrase originated in blackface minstrelsy, Lott says that it’s almost “perversely accurate … that it should come to be the name for official segregation and state-sponsored racism.”

“I think probably in the popular white mind,” he says, “it was just used because that’s just how they referred to black people.”

“Sometimes in history a movie comes out or a book comes out and it just changes the language … and you can point at it,” says David Pilgrim, Director of the Jim Crow Museum and Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion at Ferris State University.

“And in just this case,” he says, “I think it just evolved. And I think it was from many sources.”

However it happened, the new meaning stuck. Blackface minstrelsy’s popularity faded (but never died) and T.D. Rice is barely remembered. Most people today don’t know his name. But everybody knows Jim Crow.