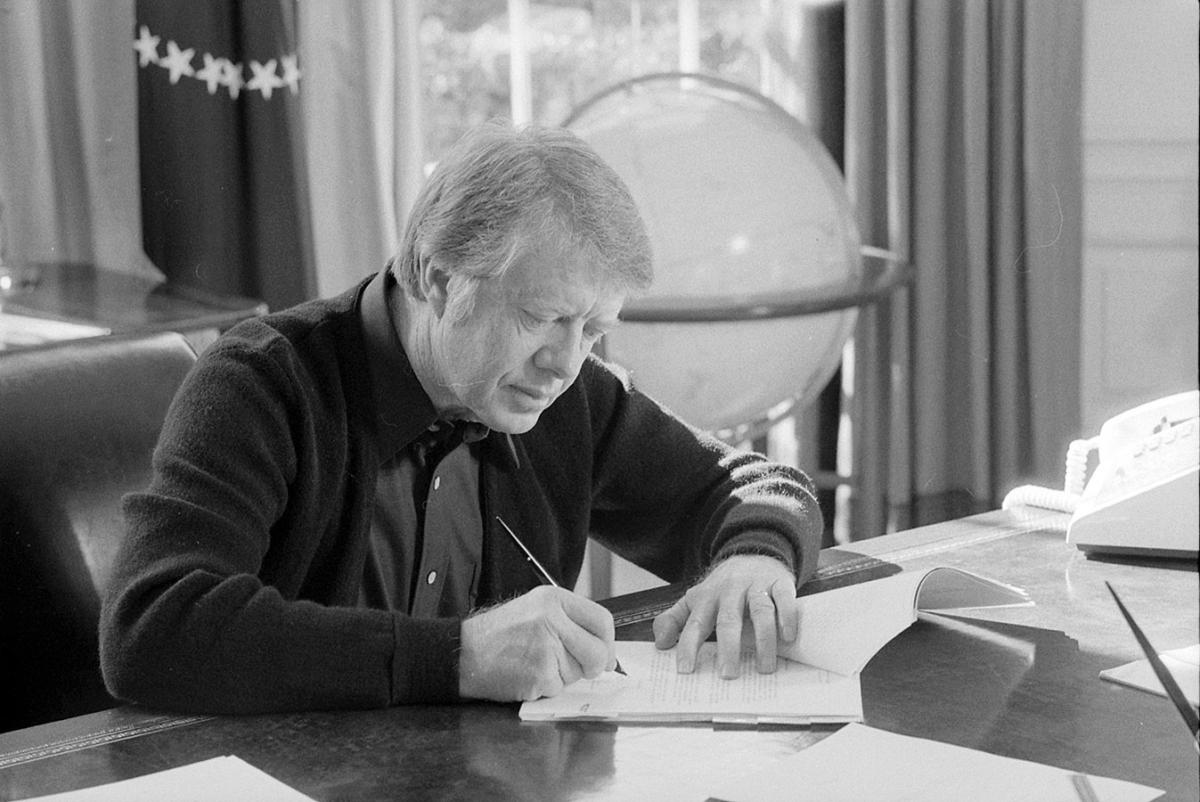

President Jimmy Carter annotates a document while working at his desk in the Oval Office" />

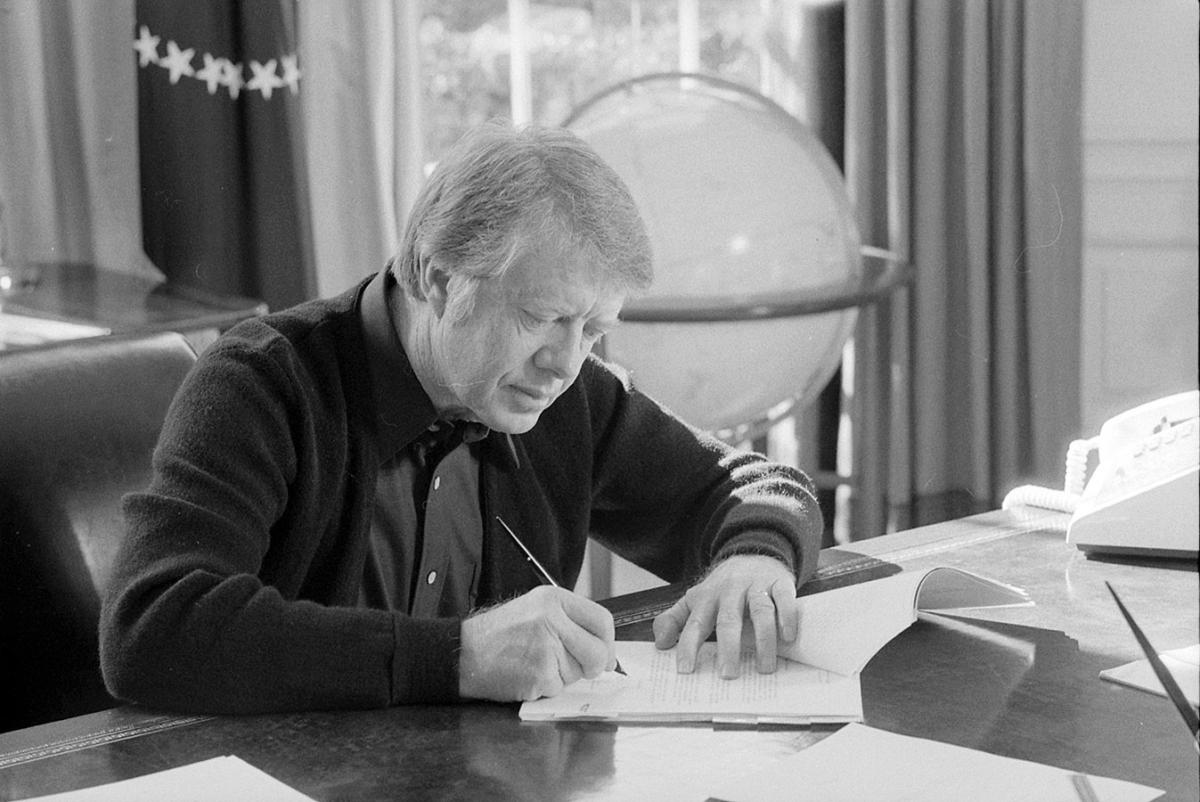

President Jimmy Carter annotates a document while working at his desk in the Oval Office" /> President Jimmy Carter annotates a document while working at his desk in the Oval Office" />

President Jimmy Carter annotates a document while working at his desk in the Oval Office" />

Carter, the mediator, observes an exchange between Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat during a break at Camp David, September 5, 1978 (White House photographer William Fitz-Patrick)

President Carter, former President Richard Nixon, and Chinese Deputy Premier Deng Xiaoping at the White House, January 29, 1979, shortly after the two powers established formal diplomatic relations on January 1 (Bettman/Corbis reproduced at Richard Nixon Foundation)

President Carter and Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev sign the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks II treaty in Vienna, Austria, June 17, 1979. The subdued expressions on the American side reflect the ambivalence of many observers that accompanied the event. (Center for Strategic and International Studies (Flickr account))

Hide/Unhide SectionWashington, D.C., December 14, 2023 – The National Security Archive is pleased to announce the publication of a major primary document collection on the presidency of Jimmy Carter. The latest in the Archive’s award-winning Digital National Security Archive series, U.S. Foreign Policy in the Carter Years, 1977-1981: Highest-Level Memos to the President comprises more than 2,500 communications and top-level policy-making records that Carter personally viewed and, in many cases, commented on directly.

More specifically, the collection features every declassified weekly memo to the president from his most senior foreign policy aides, National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski and Secretaries of State Cyrus Vance and Edmund Muskie; as well as every available meeting record of the National Security Council and its two subgroups—the Policy Review Committee and the Special Coordination Committee.

The records of Brzezinski, Vance, and Muskie (and sometimes Acting Secretary Warren Christopher) constitute a unique subset of documents that were sent directly and regularly to the president by his closest foreign policy advisers. Unlike most other message traffic to Carter, these memos did not pass through institutional filters (such as the secretariats of the State Department and National Security Council) and were intended for the president’s eyes only. The NSC meeting records are included because they comprise another highly restricted avenue for decision-making utilized by Carter.

Of special interest to readers, many of the records have the president’s own handwritten annotations, which show his unfiltered thoughts and reactions to events, policy options, and opinions floated by his top advisers.

Topics cover the gamut of foreign policy issues during this pivotal period, notably the conflict in the Middle East, the Iran hostage crisis, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, SALT talks with Moscow, the opening of diplomatic relations with China, the Nicaraguan revolution, energy, and a growing emphasis, championed by Carter, on global human rights in U.S. foreign policymaking.

Among the highlights is a record that sheds light on the ongoing historical question about the nature and extent of support the Carter administration provided to the Afghan rebels. Attached to Brzezinski’s summary of a December 28, 1979, meeting on Iran and Afghanistan is a copy of the original Presidential Finding, signed by Carter, authorizing covert action in the form of “lethal military” aid to “the Afghan opponents of the Soviet intervenion.”[1]

Among other highlights from the collection posted today are:

Electoral politics are front and center in another fascinating memo where Brzezinski describes various ways that President Carter could use his foreign policy powers to “significantly influence the outcome of the [1980] elections.” Lacking the pretext for a “sudden and dramatic stroke” that might turn the tide in the election, Brzezinski suggests that Carter attack the foreign policy proposals of Republican nominee Ronald Reagan as “escapist and dangerous” and that he consider making bold policy initiatives in Iran or Afghanistan.

The timing of this publication is fitting. In the years since he left office, Carter (like Presidents Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush before him) has undergone a number of reassessments, as recently as in the past two years, which have presented a much more positive portrayal of the 39th president than previous evaluations. The best-known of the recent biographies are Kai Bird’s The Outlier: The Unfinished Presidency of Jimmy Carter (Crown, 2021), Jonathan Alter’s His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life (Simon & Schuster, 2021), and longtime adviser Stuart E. Eizenstat’s President Carter: The White House Years (Thomas Dunne Books, 2018).

These biographies generally praise Carter for his intelligence as well as his principled stand on certain issues. These assessments are backed up by the documentary record which, while giving plenty of grist to policy critics, also shows a president who was extremely well-informed about many of the minutiae of international politics, confident in his views, tough-minded, and not intimidated by critics.

The 2,500 documents that make up U.S. Foreign Policy in the Carter Years, edited by Autumn Kladder, come primarily from the files of the Jimmy Carter Library, as well as from Freedom of Information Act requests and other sources. They offer a broad overview of his administration’s approach to the fraught arena of international affairs in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It was a time of transition—before the great changes in Cold War arch-rival USSR, initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev, that culminated in the collapse of Soviet-led Communism, but already marked by the crumbling of Moscow’s economic strength and international clout. The Carter years also saw the emergence of new political phenomena like Islamic fundamentalism, milestone events such as the end of the apartheid regime in South Africa, and the steady rise of China as a global power.

Several of these episodes—the upheavals in the Middle East and Central America, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the continuing oil crisis—were undeniably tests that Carter and his team seemed poorly equipped to handle, and these undoubtedly contributed to his electoral trouncing by Ronald Reagan after just one term. (Biographer Jonathan Alter describes him as “a famously unlucky president.”[2]) But a number of them were unalloyed successes: the Camp David accords; the breakthrough in diplomatic relations with China; the SALT II treaty; the Panama Canal treaty. In the opinion of increasing numbers of observers, including Alter, those accomplishments outweighed the fiascoes and misfortunes—some of which did not play out until his final year in office—that Carter’s administration endured.

Along the way, Carter made his mark in other, often underappreciated, ways: for example, establishing human rights as a principle of U.S. policy (if unevenly applied); recognizing the global environment as a critical priority; and providing unheralded yet essential support to the Solidarity movement in Poland. All of these issues are at the core of the revealing records in the DNSA collection, along with the rest of the panoply of world affairs which so occupied the Carter administration during his four-year term.

“These personal memos from Jimmy Carter’s closest advisers show the policy process unfolding in real time,” said Malcolm Byrne, the Archive’s research director. “Being able to read the president’s handwritten comments gives us an extraordinary window into his thinking on a slew of critical issues.”

Published by ProQuest, part of Clarivate, the new collection is available through the Digital National Security Archive series, which provides access to primary-source documents on U.S. foreign policymaking during the Cold War and beyond.