Party wall agreements are an element of extending and renovating you might need to know about. Confused by the legalities? Expert property renovator Michael Holmes explains what is involved and the rules of the Party Wall Act

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

Party wall agreements are something you need to know about it you’re planning an extension or renovation next to an adjoining property in England or Wales. The Party Wall Act 1996 is designed to help you undertake work – providing access to neighbouring properties – while protecting the interests of your neighbours.

Find out everything you need to know, from what the Party Wall Act is to complying with the act, issuing a written notice and how to find a surveyor, with our handy guide to party wall agreements.

Find out more about extending a house and renovating a property on our dedicated pages.

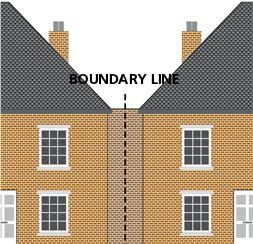

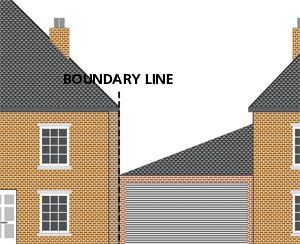

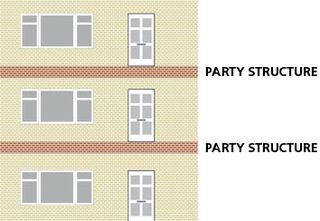

A party wall agreement, covered by the Party Wall Act covers shared walls between semi-detached and terraced houses, or structures such as the floors between flats or maisonettes, plus garden boundary walls. In addition to alterations affecting the structures directly, the effect of any excavations within 3 to 6 metres of the boundary can be covered by the Act if the foundations are considered to be likely to have an impact (based on depth).

In other words, if you'll be doing structural work on a wall you share with your neighbours, you need a party wall agreement.

A party wall agreement usually includes:

The most commonly used rights granted are:

While failing to observe the act is not an offence, your neighbours can take civil action against you and have an injunction issued to stop further work until a party wall agreement is arranged. This will delay your project and is likely to increase your costs – your builder may demand compensation for the time they cannot work, or may start another job and not return for several months.

Your neighbours may seek compensation if they can prove they have suffered a loss as a result of the work, and it could even require removal of the work. The same applies if you have a party wall agreement with your neighbours but fail to observe the terms agreed.

If building work affects a party structure, you must serve notice at least two months before work begins. In the case of excavations, you must give at least one month’s notice. Work can begin once an agreement has been entered into.

You need to write to all adjoining homeowners, stating your name and address, a full description of the work, including the property address and start date, plus a statement that it is a Party Wall Notice under the provisions of the Act.

Before serving notice, chat to your neighbours about your plans and make sure they understand what it is you are planning to do.

You serve notice on your neighbour by writing to them and including your contact details and full details of the works to be carried out, access requirements and the proposed date of commencement. In an urban environment, your project might affect several adjoining neighbours, and you will have to serve notice on each of them. If a property is leasehold you will need to serve notice on both the tenant and the building’s owner.

Provide your neighbour with details of the Party Wall Act so that they know what they are agreeing to – downloading the Planning Portal's explanation of the Party Wall Act is the best way around this.

Your neighbour has 14 days to respond and give their consent, or request a party wall settlement. If they agree to the works in writing, you will not require a party wall agreement and this can save on the fees, which are typically £700 to £900 per neighbour. It therefore pays to contact your neighbours first to discuss your proposals and to try to overcome any issues in advance, or at the very least ensure they receive the notice and respond within 14 days, because if they fail to, they are deemed to be in dispute and you will need to instruct a surveyor anyway, whether they consent to the works or not.

You can use this party wall template letter from the HomeOwners Alliance to send to your neighbours.

It’s always a good idea to discuss proposals in advance of serving notice. If you get your neighbour on board, they may simply consent to the work (but you’ll need this in writing) and you’ll incur no fees.

You will still have to comply with the terms of the Act, for example avoiding unnecessary inconvenience, providing temporary protection for adjacent buildings and properties where necessary and compensating your neighbour for any loss or damage if it is caused by the work.

If they refuse or fail to respond, you are deemed to be in dispute; if this happens, you can contact the owner and try to negotiate an agreement.

They may write to you and issue a counter-notice, requesting certain alterations to the work, or set conditions such as working hours. If you can reach agreement, put the terms in writing and exchange letters, work can begin.

If you fail to reach an agreement, you’ll need to appoint a surveyor to arrange a Party Wall Award that will set out the details of the work. Hopefully, your neighbour will agree to use the same surveyor as you – an ‘agreed surveyor’ so it will only incur a single set of fees. However, your neighbour has the right to appoint their own surveyor at your expense.

If each side’s surveyor still cannot agree, you have to pay for a third surveyor to adjudicate.

If you require an Award, it can cost from £700 to £900 per surveyor. If you have several adjoining homeowners, each insisting on using their own surveyor, the fees can be quite considerable, so reasoned negotiation is always advisable.

If you fail to issue a Party Wall Notice before the relevant work begins, or fail to secure a Party Wall Award, your neighbour can serve an injunction to stop or prevent the work that will affect their property, until the Award is in place.

If you comply with the Act, however, they can’t prevent the work from going ahead, or deny you access to their property to undertake the work.

Part 3 of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 places a duty on a local authority to investigate complaints of statutory nuisance from people living within its area. This includes complaints about noise and dust from building work where it unreasonably interferes with the use or enjoyment of their premises or is prejudicial to their health.

The local authority will always encourage adjacent landowners to resolve matters amicably – for instance by scheduling deliveries or works for only certain hours of the day and restricting work carried out on Sundays and Bank Holidays. If the local authority decide to take enforcement action, you are advised to comply with this, as contravention can lead to prosecution.

The Party Wall etc. Act 1996 only applies to England and Wales. Scotland and Northern Ireland rely on common law rather than legislation to settle party wall disputes. Neighbouring owners can negotiate to allow work to proceed – and access can be forced through the courts if necessary.

If you are extending a property close to a neighbour and this will significantly reduce the light that reaches their plot and passes through their windows, you may be infringing their right to light. This could give them the right to seek an injunction to have your proposed development reduced in size or to seek a payment to compensate for the reduction of light.

If the loss of light is small and can be adequately compensated financially, the court may award compensation instead of an injunction. However, if you have built without consideration for your neighbour’s right to light and are found to have infringed their right, the court has the power to have the building altered or removed at your expense.

In England and Wales, a right to light is usually acquired by prescription – in other words, once light has been enjoyed for an uninterrupted period of 20 years through the windows of the building. Once acquired, the right to light extends only to a certain amount of light such as is suitable for the continuous use and enjoyment of the building, and is not a right to all the light that was once enjoyed.

This means the right to light can be reduced by development – there is no assumption that any reduction in light to your neighbour’s property gives grounds for them to prevent your development. Specialist computer software programmes are used to calculate mathematically whether or not a development causes an infringement, and the results are used to determine whether any compensation might be payable and, if so, how much.

Your neighbour’s right to light is not diminished or reduced by the fact that the local authority have granted you planning permission for your project, or because your intended project constitutes permitted development and so does not require planning permission.