The rise of the European merchant class was accompanied by a questioning of traditional power structures and leadership roles that no longer belonged exclusively to royalty and the church. At the same time, the arrival of the Enlightenment fostered novel ideas about the role of the press, free speech, religious liberty, and self-government. These shifting power dynamics, combined with rising literacy rates and new printing and engraving technologies yielded a climate ripe for the creation of political cartoons, and the events of the eighteenth century were the first to be lampooned.

It wasn’t long before political cartoons reached the New World, though under British rule a person who criticized the crown or the government might be imprisoned. By the end of the American Revolution, however, political cartoons had become relatively common, and with the ratification of the Bill of Rights in 1791, American rights to create political cartoons through free speech and the free press were protected by the First Amendment. Political cartoons in this era commented on social, cultural, and political issues on both a local and national level, and were often published and sold independently, rather than as a part of a newspaper or periodical.

Click on each image to enlarge.

Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme

William Hogarth, 1721, London, England

In 1720, the collapse of the South Sea Company, which dealt in slave ships and trade with South America, spawned numerous political cartoons in the Netherlands and Britain. These are among the first recognizable political cartoons by today’s standards, characterized by symbolism, exaggerated characters, metaphor, and more.

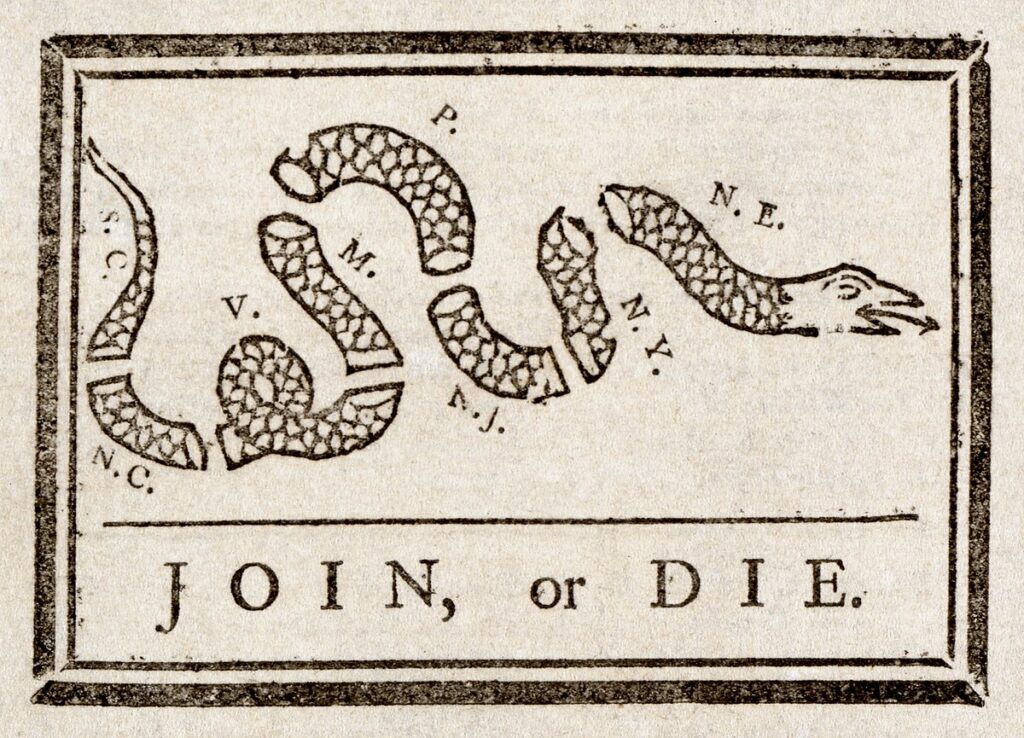

Join, or Die

Benjamin Franklin, 1754, for the Pennsylvania Gazette, Pennsylvania, British Empire

One of the earliest and most famous examples of American political cartoons is this woodcut showing a snake cut into eighths, with each segment labeled with the initials of one of the American colonies or regions. The cartoon, which first appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette in May of 1754, became a symbol of the need for organized action against the threat posed by the French and their native allies during the Seven Years’ War. It has been an enduring American symbol ever since.

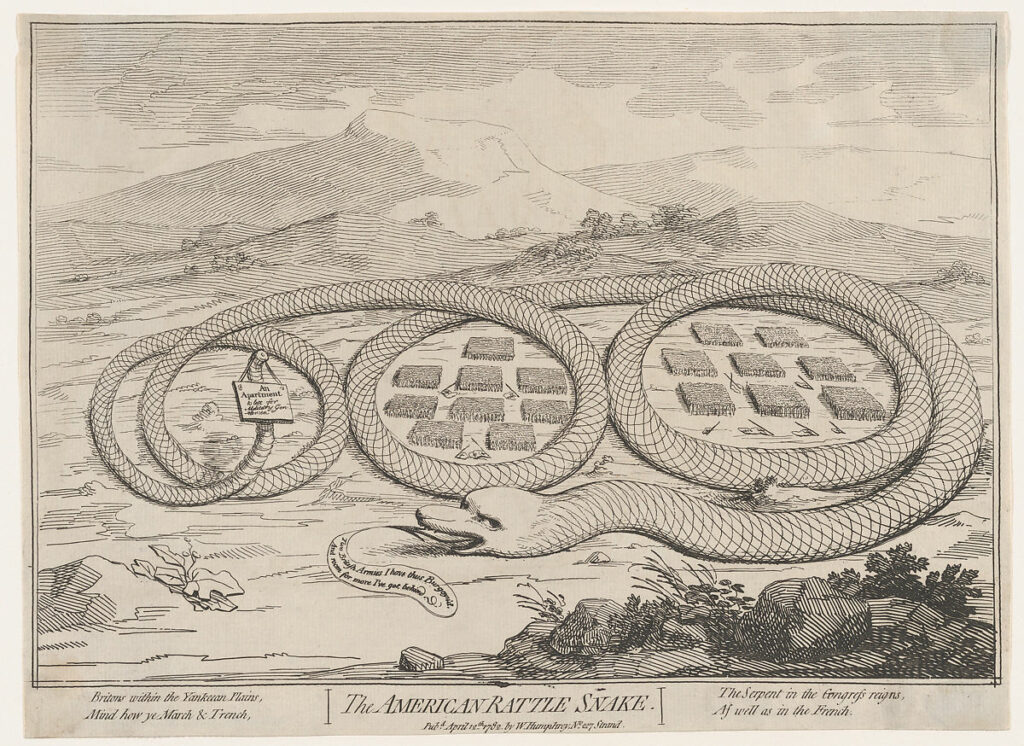

The American Rattle Snake (sic.)

James Gillray, 1782, London, England

This cartoon references Benjamin Franklin’s Join, or Die by showing the “American Rattle Snake” surrounding British armies at Yorktown, the site of Britain’s final defeat during the American Revolution.

The British Lion Engaging Four Powers

J. Barrow, 1782, London, England

The snake, the seemingly favorite animal representation of America during the Revolution, is joined by a spaniel representing Spain, a chicken representing France, and a pug representing the Netherlands, as they square off against the British lion. Spain, France, and the Netherlands had all supported the new United States during the Revolution.

The Looking Glass for 1787

Amos Doolittle, 1787, New Haven, Connecticut

Two rival factions are lampooned here – the Federalists, who were in favor of the Constitution, and the Anti-Federalists, who were skeptical of the Constitution. In this cartoon, both sides tug on a wagon representing Connecticut on the eve of the ratification of the Constitution.

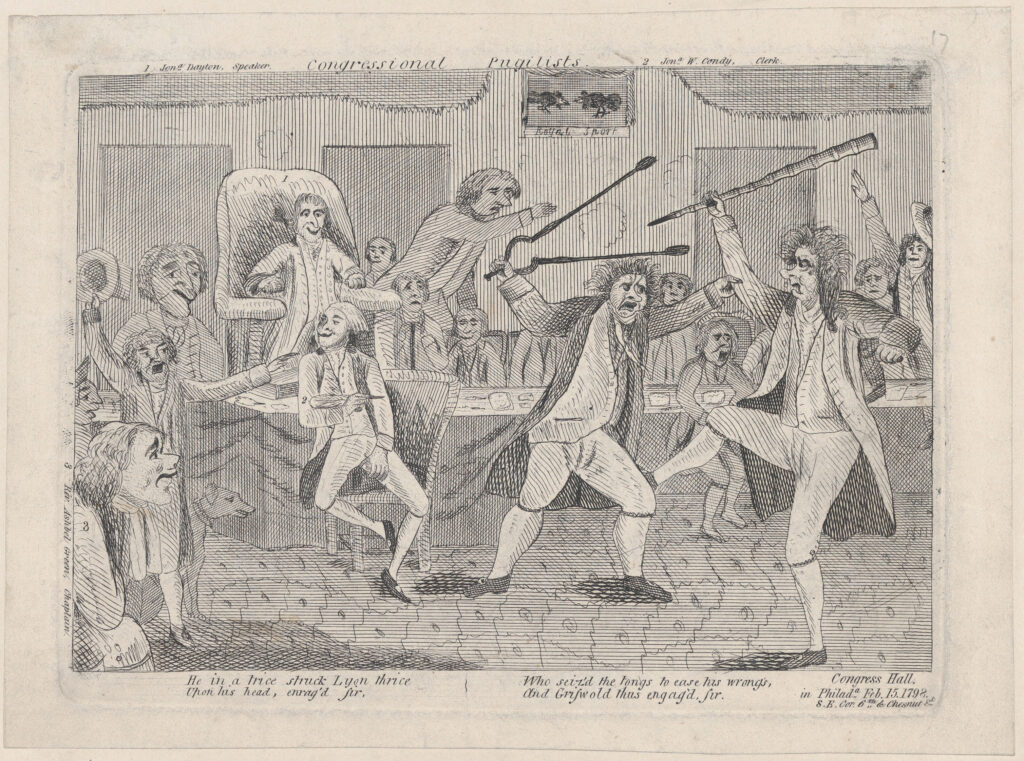

Congressional Pugilists

Artist unknown, 1798, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

This cartoon portrays a fight on the floor of Congress between Vermont Representative Matthew Lyon and Roger Griswold of Connecticut. With tensions already high due to the controversy over the 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts, the fight was ignited by an insult from Griswold to Lyon. Griswold, armed with a cane, kicks Lyon, who grasps the former’s arm and raises a pair of fireplace tongs to strike him.